48 ISE Magazine | www.iise.org/ISEmagazine

Improving patient treatment,

satisfaction at a small hospital

Monroe County Hospital is a critical access hospital located in

Forsyth, Georgia. It is a 25-bed facility comprising an emer-

gency department (ED) and medical-surgical unit that cares for

inpatient and rehabilitation patients. The ED sees just over 8,500

patients annually from six counties in middle Georgia. This hos-

pital has been providing access to high quality health services to

the citizens of Monroe County since 1954 when the hospital au-

thority was founded (monroehospital.org/about/history-and-mission.

cms).

In 2016, this facility became a strategic partner of Navicent

Health based in Macon, Georgia. In 2018, Monroe County Hos-

pital became DNV GL accredited and was on track to become

ISO 9001:2015 certified this spring. In 2019, the team embarked

on the high-performance journey in the spirit of continuous im-

provement. As part of the certification process, the leadership

team set out to identify and eliminate any and all types of waste

plaguing the hospital’s operational environment.

These initial efforts focused on delays in the emergency de-

partment wait times. This is significant because such delays un-

favorably impact quality of care, revenues and customer satisfac-

tion levels when patients leave without treatment. The ultimate

goal was to provide safer and more effective care to all patients.

The team was sponsored by the CEO, who is an IISE-trained

Black Belt, along with other leaders. The project was initiated

in January 2019 and concluded December 2019. But outcomes

are still monitored and adjustments made as needed to ensure

“wins” are sustained long term. The team used a standard DMA-

IC methodology to define the problem, measure the current state,

analyze the data, improve the noted issues and control the changes

long term. Moreover, many cross-functional stakeholders were

included in the process to ensure the improvements were maxi-

mized, sustained and culturally adopted.

The process, project and outcomes

Define. Extended wait times and subsequent alarm about pa-

tients who leave emergency departments without treatment has

become a mounting national concern. In January 2019, the proj-

Solutions in practice by Chasatie Whitley,

Casey Fleckenstein, Lorraine Smith, Hershel

Kessler and Casey Bedgood

case study

May 2021 | ISE Magazine 49

case study

ect team developed and implemented a method to decrease

wait times and thus the number of patients who left with-

out being treated (LWOT). According to the Community

Health Needs Assessment of 2016, access to care was iden-

tified as a need in our community. The team interpreted

that the low ED volume, increased wait times and increased

LWOT rates indicated that patients were seeking emergen-

cy treatment elsewhere in our region. This decreases their

access to care within the community and unfavorably im-

pacts revenues.

The focus of the project was on reducing LWOTs in the

emergency room. These patients are an issue for a variety

of reasons. First, delays in care represent waste and result

in patients seeking treatment at alternate care sites. This

inhibits access to care, reduces quality of care and nega-

tively impacts patient satisfaction and revenues. Moreover,

if customers cannot receive services when, where and how

they desire them, the hospital’s reputation will be less than

favorable.

The goal of the project was to initially reduce LWOTs

monthly to the national benchmark of 2% or less (Medicare.

gov, 2018). Long term, the ideal goal was zero LWOTs each

day. Unfortunately, the rate for Monroe County Hospital

was over 2% on average in 2018. Also, the team focused on

increasing patient satisfaction levels to the national bench-

mark. The initial goal was 75% favorable each month.

It’s important to note that if goals are not consistently

achieved, volumes, quality of care, customer satisfaction

and revenues will continue to decline. Moreover, the pub-

lic’s perspective of the organization would be further im-

pacted.

Measure. The main key performance indicators chosen

by the team were monthly LWOT rates and patient satis-

faction scores (percent favorable). The desired trend is to

achieve fewer LWOTs and higher patient satisfaction scores

each month. Both metrics were measured monthly over a

year before the project began. Post project, the results were

measured monthly for over a year as well to ensure the sus-

tainment of wins. Figure 1 shows performance to goal for

both metrics before the project showing that patient sat-

isfaction scores were meeting goal only 20% of the time.

The LWOT scores were only meeting goal 47% of the time

pre-project for the same time period.

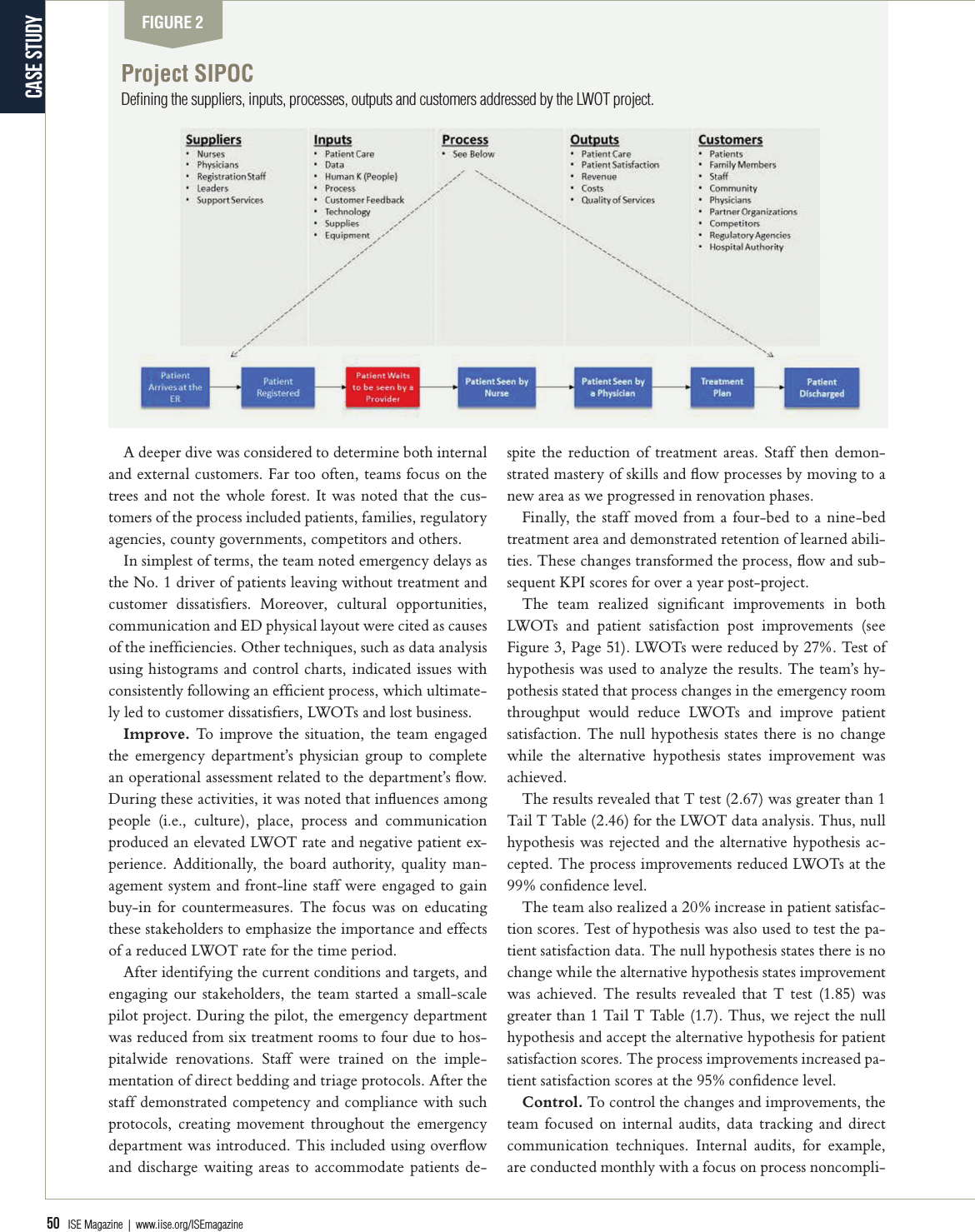

Analyze. To analyze the current state, the team started

with a high-level process map (i.e., SIPOC; shown in Figure

2, Page 50). The team used the SIPOC to identify the suppli-

ers, inputs, process, outputs and customers of the ED process.

The suppliers represented various stakeholders ranging from

leadership to front-line staff. These stakeholders would be

crucial in addressing the waste and inefficiencies. The inputs

related to items such as people, training, data, equipment and

more. The outputs were very straightforward: clinical care,

quality, revenue and customer satisfaction.

FIGURE 1

Pre-project KPI graphs (actual versus goal)

Performance metrics before the project showed that patient satisfaction scores and patients leaving without treatment numbers were below

the goals set.

Leaders must measure, track and know

their organization’s numbers. Data is

like a sheet of music that will tell you

exactly where the problem is when you

know how to interpret it.

50 ISE Magazine | www.iise.org/ISEmagazine

case study

A deeper dive was considered to determine both internal

and external customers. Far too often, teams focus on the

trees and not the whole forest. It was noted that the cus-

tomers of the process included patients, families, regulatory

agencies, county governments, competitors and others.

In simplest of terms, the team noted emergency delays as

the No. 1 driver of patients leaving without treatment and

customer dissatisfiers. Moreover, cultural opportunities,

communication and ED physical layout were cited as causes

of the inefficiencies. Other techniques, such as data analysis

using histograms and control charts, indicated issues with

consistently following an efficient process, which ultimate-

ly led to customer dissatisfiers, LWOTs and lost business.

Improve. To improve the situation, the team engaged

the emergency department’s physician group to complete

an operational assessment related to the department’s flow.

During these activities, it was noted that influences among

people (i.e., culture), place, process and communication

produced an elevated LWOT rate and negative patient ex-

perience. Additionally, the board authority, quality man-

agement system and front-line staff were engaged to gain

buy-in for countermeasures. The focus was on educating

these stakeholders to emphasize the importance and effects

of a reduced LWOT rate for the time period.

After identifying the current conditions and targets, and

engaging our stakeholders, the team started a small-scale

pilot project. During the pilot, the emergency department

was reduced from six treatment rooms to four due to hos-

pitalwide renovations. Staff were trained on the imple-

mentation of direct bedding and triage protocols. After the

staff demonstrated competency and compliance with such

protocols, creating movement throughout the emergency

department was introduced. This included using overflow

and discharge waiting areas to accommodate patients de-

spite the reduction of treatment areas. Staff then demon-

strated mastery of skills and flow processes by moving to a

new area as we progressed in renovation phases.

Finally, the staff moved from a four-bed to a nine-bed

treatment area and demonstrated retention of learned abili-

ties. These changes transformed the process, flow and sub-

sequent KPI scores for over a year post-project.

The team realized significant improvements in both

LWOTs and patient satisfaction post improvements (see

Figure 3, Page 51). LWOTs were reduced by 27%. Test of

hypothesis was used to analyze the results. The team’s hy-

pothesis stated that process changes in the emergency room

throughput would reduce LWOTs and improve patient

satisfaction. The null hypothesis states there is no change

while the alternative hypothesis states improvement was

achieved.

The results revealed that T test (2.67) was greater than 1

Tail T Table (2.46) for the LWOT data analysis. Thus, null

hypothesis was rejected and the alternative hypothesis ac-

cepted. The process improvements reduced LWOTs at the

99% confidence level.

The team also realized a 20% increase in patient satisfac-

tion scores. Test of hypothesis was also used to test the pa-

tient satisfaction data. The null hypothesis states there is no

change while the alternative hypothesis states improvement

was achieved. The results revealed that T test (1.85) was

greater than 1 Tail T Table (1.7). Thus, we reject the null

hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis for patient

satisfaction scores. The process improvements increased pa-

tient satisfaction scores at the 95% confidence level.

Control. To control the changes and improvements, the

team focused on internal audits, data tracking and direct

communication techniques. Internal audits, for example,

are conducted monthly with a focus on process noncompli-

FIGURE 2

Project SIPOC

Defining the suppliers, inputs, processes, outputs and customers addressed by the LWOT project.

May 2021 | ISE Magazine 51

If you’ve been involved in a project that put solutions to the test in a

real-world environment, it could be a potential Case Study article. Please

send your idea to Managing Editor Keith Albertson at kalbertson@iise.org

for consideration.

Do you have a Case Study to share?

ance. These teams journey to the gemba, where the work

happens, to assess if processes are being followed consistent-

ly. If issues are noted, the respective leaders must initiate

a corrective action plan immediately for resolution. Then,

teams reaudit to ensure corrections were successful.

Second, the team tracks data monthly for all KPIs against

national benchmark goals. If goals are not attained, the data

is communicated to senior leaders, the board and quality

management system for magnification and resolution.

Finally, both vertical and horizontal communication

techniques are used to ensure all stakeholders are apprised

of and track the current environment. If changes are need-

ed, the goal is to make interventions in real time when

possible.

Lessons learned

There are several pearls the team learned from the project.

First, the voice of the customer is always a great starting point

for any improvement project. Always focus on the customer

and be able to answer: What do they want, need and expect

from the organization? If gaps exist, teams should focus on

measuring, validating and correcting the gaps.

Second, leaders must measure, track and know their or-

ganization’s numbers. Data is like a sheet of music that will

tell you exactly where the problem is when you know how

to interpret it. The team learned that it’s better to initiate

data-driven interventions sooner than later.

Third, the gemba should always be a focal point when

solving process-related issues. Go to where the work is be-

ing done, talk to those closest to the process to understand

the issues and incorporate those at the gemba in the solution

process.

Finally, there is no substitute for a good process. Good

processes or lack thereof can make or break an organiza-

tion, particularly in healthcare. The team learned that

starting with a sound, data-driven process, measuring the

process outcomes regularly, auditing the process routinely

(not just the activities being performed) and real-time cor-

rections of nonconformities are paramount in meeting and

exceeding customer requirements.

Chasatie Whitley, BSN, RN, CEN, is process owner for Navi-

cent Health.

Casey Fleckenstein, BSN, RN, is nurse director and an IISE-

trained Lean Six Sigma Green Belt for Navicent Health.

Lorraine Smith, MBA, MT(ASCP)SH, is CEO, executive

sponsor and an IISE-trained Black Belt. Contact her at Lorraine.

Smith@atriumhealth.org.

Hershel Kessler, DO, is emergency department medical director for

Navicent Health.

Casey Bedgood, MPA, CSSBB, is the system accreditation op-

timization officer at Navicent Health and an IISE-trained Lean

Green Belt, Six Sigma Green Belt and Six Sigma Black Belt. He

was an adviser and Black Belt sponsor for this project. He is an

IISE member.

FIGURE 3

Postproject KPI improvements

Results show significant improvements in the number of patients leaving without treatment (down 27%) and increased patient satisfaction.